Prabhash Chandra’s sophomore, Alaav (Hearth and Home), hits home. It is a sudden realisation that I am getting older, as is my mother. Will I be able to take care of her in her late years the way she has of her parents, the way this film’s protagonist does? The 60-something Bhaveen Gossain’s routine caretaking of his 90-something mother, Savitri, is an unceasing act — an unseen and thankless one — day in and day out. The film is an ode to the complex task of caregiving. In this cinéma-vérité outing, Gossain, a classical Kasur–Patiala gharana vocalist and actor, and his mother, Savitri, are real-life mother and son.

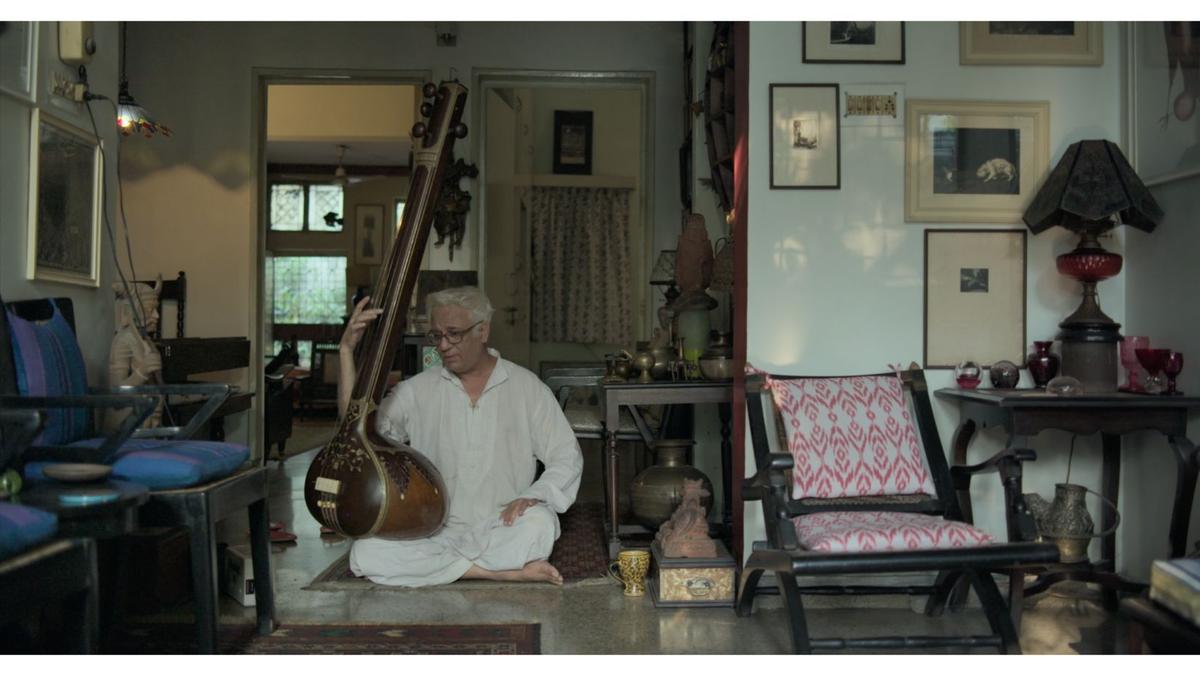

For about five minutes, we watch Gossain immersed in his Hindustani classical riyaaz, setting the film’s mood with Raga Bhoopali—an uplifting, calm, and devotional evening raga. The static camera is placed in the adjacent room, and we see the subject through the connecting doorway— it’s a frame within a frame. And then, we see him putting his mother to bed and feeding her. He reads to her, removes her dentures, wipes the floor, bathes her, and helps her with her bowel movement. These rituals of everyday life unfold quietly, as he gently reminds her of his name and their relationship from time to time.

Alaav means an open fire, lit outdoors, to provide warmth during winter nights. This film, too, feels like a warm hug on a cold night. It was screened at the recently concluded 30th International Film Festival of Kerala (IFFK) in the Indian Cinema Now segment. The movie had premiered at France’s Festival des 3 Continents and the Dharamshala International Film Festival.

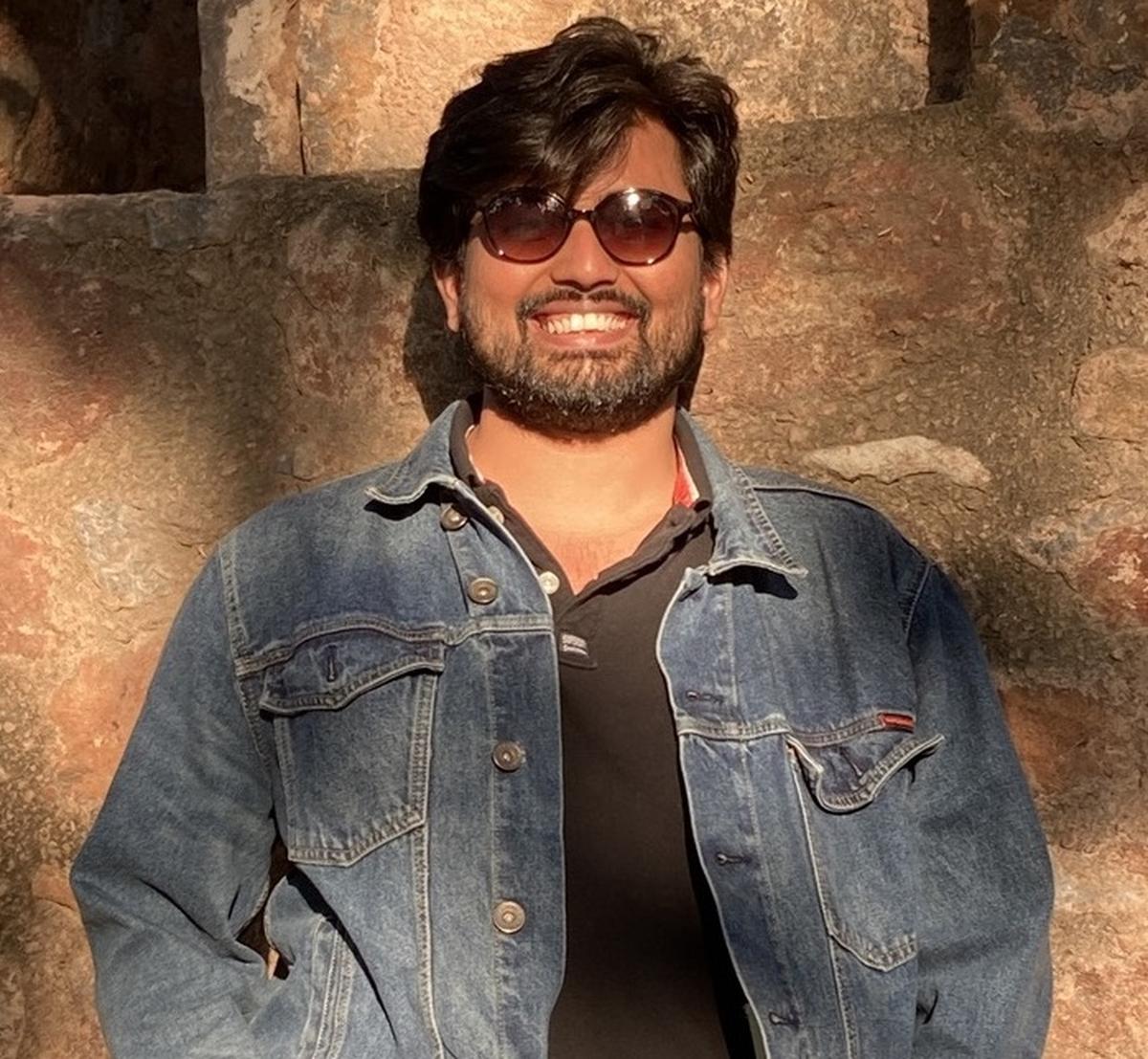

Alaav director Prabhash Chandra

| Photo Credit:

Special Arrangement

During his days at the Delhi University, Chandra was working on a play when he went to meet Gossain, the classical singer. What started with some breathing exercises led to an experience that resulted in the film. One day, Gossain requested Chandra to come and hold the fort at his home while he stepped out to buy things. He left his mother under Chandra’s supervision.

That was the start of spending longer periods of time with Savitri. “She was very funny and nice in many ways,” he says, “She would joke and ask me to persuade Bhaveen to get married.” Savitri passed away last winter. To Chandra, it struck a personal chord. Those moments with Gossain’s mother were fragile remembrances of his own life in his village, which he left in 2008. “I go into a bad space when I think about these things because I’m unable to give time to my mother,” he adds.

This could have been his first film, but it took five years to make. Gossain was initially apprehensive about featuring in a film again, after his sour experiences in Bollywood. He worked in a few films, including Rajan Khosa’s Dance of the Wind (Swara Mandal, 1997) and another movie by Kabir Mohanty. But he got excited when Chandra sent footage rushes in 2020 from the Pulwama schedule of his film on Kashmir, I’m Not the River Jhelum. Set in the period following the abrogation of Article 370, the film went on to win the FFSI K. R. Mohanan Award for Best Debut Director at the IFFK 2022. “What I saw in Kashmir made it impossible for me to look away,” says Chandra.

The filmmaker employed a poetic sensibility and a personal lens to speak about the state’s politics, the normalised everydayness and universality of violence (a teargas at a workshop, a family member gone missing) in his first film. The same blend of the personal and the poetic breathes life into his second film, rescuing it from devolving into bleak despair or monotony.

The title Alaav sounds a lot like alaap (when the swar/note of any Hindustani classical raga is elongated in a slow rhythm/bilambit laya). Like the music notes, scenes too are long and slow, to let its realism surface. The unhurried film is a meditation, rumination, and visual soliloquy on not just ageing, loneliness, loss and death but on life itself. “Because Savitri aunty passed away within a year after the shooting, I had decided to make a film, one where life goes on, Bhaveen, whose everyday life revolves around caring for his mother, how his life goes on in the same space after the mother has left him,” he says.

Bhaveen Gossain in a still from film Alaav (Hearth and Home).

| Photo Credit:

Special Arrangement

For this film, Chandra went to cinematographer Vikas Urs (Pedro; Shivamma), whose three other films were screened at the IFFK this year, including Sabar Bonda (Cactus Pears), Vaghachipani (Tiger’s Pond) and Secret of a Mountain Serpent. “I wanted to construct a film where everything, in terms of craft, is invisible in that space; where everything is static, and the invisible camera is just observing time and the mundanity of daily life,” says Chandra.

Chamber piece

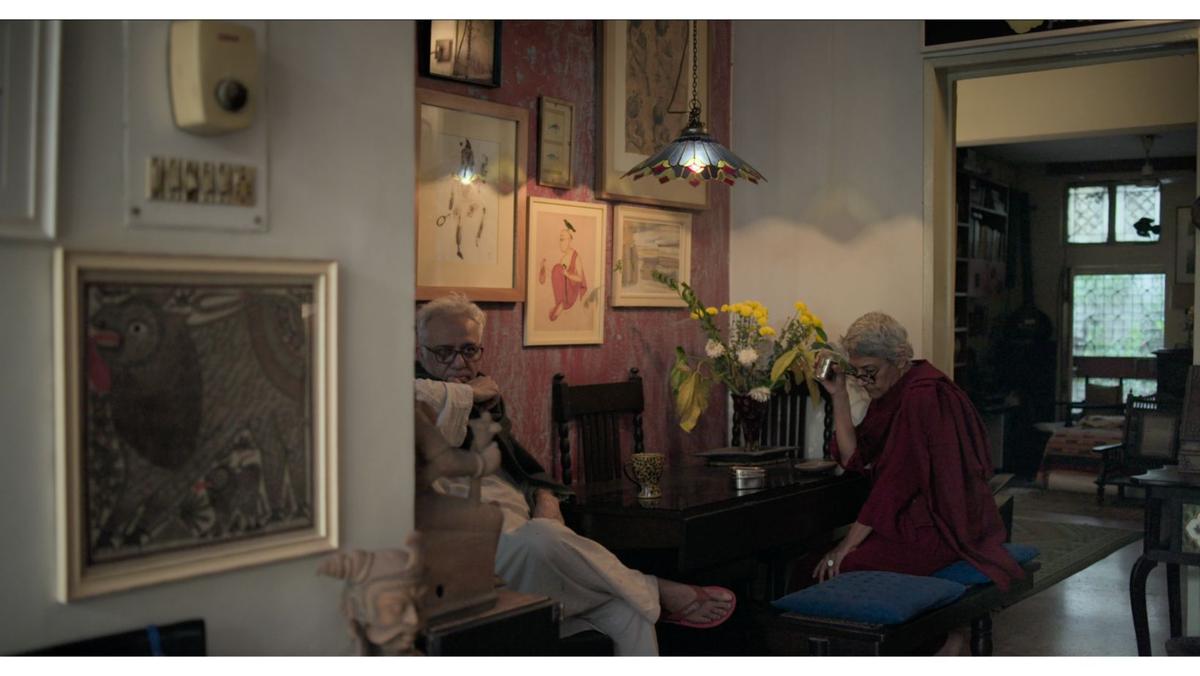

The film was shot on location, in Gossain’s own house in Delhi. And the only time we see the subjects step out is for a festival. “It was planned in my head that I want to see both of them coming out of the house just once in the film to celebrate Diwali,” he says. The house is his entire world. Remnants of the outside world come to meet him here; he almost never steps out. Time stands still in the film as one goes about the daily chores on autopilot. Time observes its own passage.

The cast is a mix of actors (Gossain and Anita Kanwar) and non-actors. Savitri had never acted before, and retakes were also not possible due to her health condition. However, she was a natural, says the director. She followed the prompts that were given to her, or just did something of her own, as the camera rolled. The breakfast scene stands out, showing the mother visibly angry after her son shouted at her the previous night. She brings the anger brilliantly as she dips a rusk in her cup of morning tea.

A still from film Alaav (Hearth and Home).

| Photo Credit:

Special Arrangement

In this chamber piece, we don’t know what is happening outside it in spatiotemporal terms. We are given no insight into Gossain’s backstory or the earlier dynamics between the mother and son—whether he had another life or a family. Rather, everything exists in the here and now.

Meditation on masculinity

Through thirty static shots, we see a welcome representation of masculinity unfold, since in patriarchal societies, caregiving is often a woman’s lot. Masculinity, here, is confronted with vulnerability; emotional repression meets tenderness, guilt, irritation, and devotion — there’s a collapse of an inherited authority. It involves submission to time, illness and decay, requiring emotional attunement rather than mastery. A quiet endurance. This perspective, of an ageing son caring for an elderly mother, is quieter, less sentimental, and more psychologically raw than daughter-focused narratives. It is a return of the pre-Oedipal bond. A role reversal.

A still from film Alaav (Hearth and Home).

In Albrecht Dürer’s artwork, Portrait of the Artist’s Mother (1514), the son does not idealise; he witnesses. He’s tolerating the mother’s fragility without collapsing into fantasy or denial. Barbara Dürer, the ageing mother — frail, ill, dependent — no longer embodies omnipotence, but pure mortality. It is a reckoning. Her decline mirrors the son’s future decline. The mother cannot save him from death, loss, or himself. This is a decisive moment of psychic separation.

This “moral masculinity”, where restraint becomes ethical depth, is reflected in Japanese filmmaker Hirokazu Kore-eda’s cinema too. (Maborosi, 1995; Still Walking, 2008; After the Storm, 2016).

Music of melancholy

“I was not making a film on someone who is a classical musician. I used the music in a way where I can draw a parallel, where both these forms demand surrender, discipline and there is both fatigue and grace at the same time. I wanted to build all those things,” says Chandra.

Sounds enter the house like visitors: birds chirping, vendors selling vegetables, a flight in motion. It is also a reminder that Gossain or his mother are stuck here. Music becomes a character in the film, accentuating the myriad emotions as it is the only escape and identity Gossain has apart from being a caregiver.

A still from film Alaav (Hearth and Home).

| Photo Credit:

Special Arrangement

As V. S. Naipaul wrote in A House for Mr Biswas, Gossain realised he is bound to his mother by a duty that would never end. Yet, he also remembered her kindness, which gave him strength—echoing Chinua Achebe’s words in Things Fall Apart. He would take care of her, as she had taken care of him, as Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o writes in Weep Not, Child.

This film is deeply reflective of expansive nuances of care. This is what art is supposed to do: reveal the wound and also offer healing.

#Alaav #review #Prabhash #Chandras #intimate #film #ageing #caregiving #quiet #masculinity